Strabismus (Crossed Eyes)

Crossed eyes, or strabismus as it is medically termed is a condition in which both eyes do not look at the same place at the same time. It occurs when an eye turns in, out, up or down and is usually caused by poor eye muscle control or a high amount of farsightedness.

There are six muscles attached to each eye that control how it moves. The muscles receive signals from the brain that direct their movements. Normally the eyes work together so they both point at the same place. When problems develop with eye movement control, an eye may turn in, out, up or down. The eye turning may be evident all the time or may appear only at certain times such as when the person is tired, ill, or has a lot of reading or close work. In some cases, the same eye may turn each time, while in other cases, the eyes may alternate turning.

Maintaining proper eye alignment is important to avoid seeing double, for good depth perception and to prevent the development of poor vision in the turned eye. When the eyes are misaligned, the brain receives two different images. At first, this may create double vision and confusion, but over time the brain will learn to lead to permanent reduction of vision in one eye, a condition called amblyopia or lazyeye.

Some babies’ eyes may appear to be misaligned, but are actually both aiming at the same object. This is a condition called pseudo strabismus or false strabismus. The appearance of crossed eyes may be due to extra skin that covers the inner corner of the eyes, or a wide bridge of the nose. Usually this will change as the child’s face begins to grow.

Strabismus usually develops in infants and young children, most often by age 3, but older children and adults can also develop the condition. There is a common misconception that a child with strabismus will outgrow the condition. However, this is not true. In fact, strabismus may get worse without treatment. Any child older than four months whose eyes do not appear to be straight all the time should be examined.

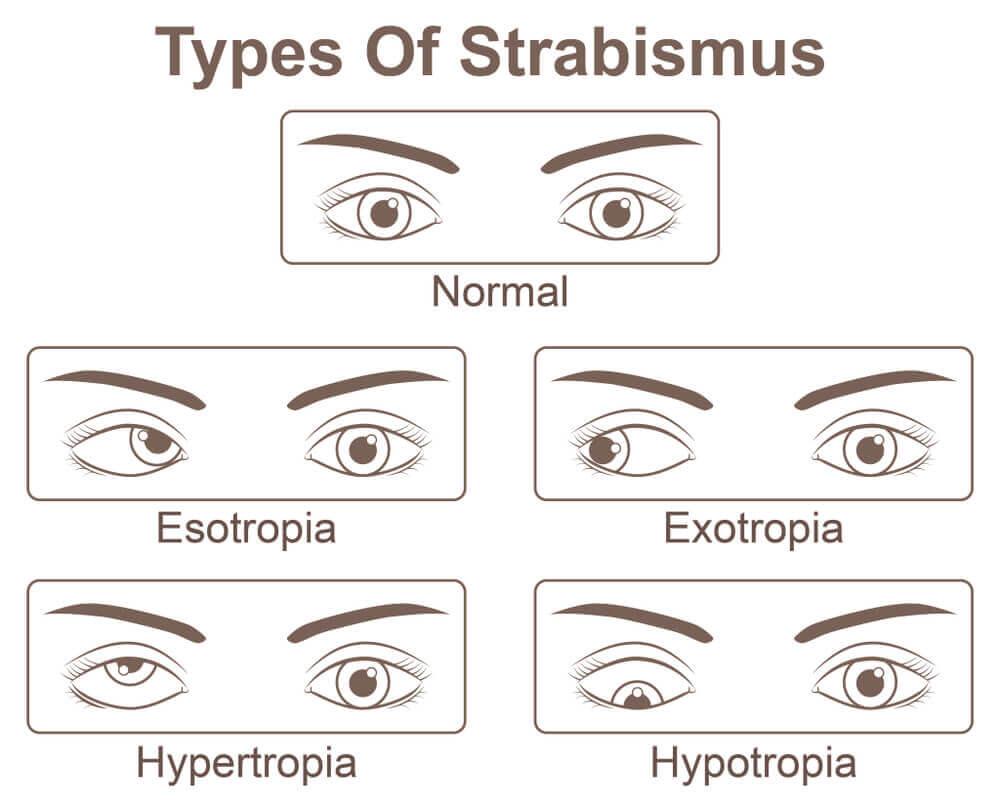

Strabismus is classified by the direction the eye turns:

- Inward turning is called exotropia

- Outward turning is called exotropia

- Upward turning is called hyperopia

- Downward turning is called hypotropia

Other classifications of strabismus include:

- The frequency with which it occurs – is either constant or intermittent.

- Whether it always involves the same eye – unilateral

- If the turning eye is sometimes the right eye and other times the left eye – alternating.

Treatment for strabismus may include eyeglasses, prisms, vision therapy, or eye muscle surgery. If detected and treated early, strabismus can often be corrected with excellent results.

What causes strabismus?

Strabismus can be caused by problems with the eye muscles, the nerves that transmit information to the muscles, or the control center in the brain that directs eye movements. It can also develop due to other general health conditions or eye injuries.

- Family history – individuals with parents or siblings who have strabismus are more likely to develop it.

- Refractive error – people who have a significant amount of uncorrected farsightedness (hyperopia) may develop strabismus because of the additional amount of eye focusing required to keep objects clear.

- Medical conditions – people with conditions such as Down syndrome and cerebral palsy, who have suffered a stroke, or head injury are at a higher risk for developing strabismus.

Although there are many types of strabismus that can develop in children or adults, the two most common forms are accommodative exotropia and intermittent exotropia.

Accommodative exotropia often occurs because of uncorrected farsightedness (hyperopia). Because the eye’s focusing system is linked to the system that control’s where the eyes point, the extra focusing effort needed to keep images clear in farsightedness may cause the eyes to turn inward. Signs and symptoms of accommodative extropia may include seeing double, closing or covering one eye when doing close work, and tilting or turning of the head.

Intermittent exotropia may develop due to an inability to coordinate both eyes together. The eyes may have tendency to point beyond the object being viewed. People with intermittent exotropia may experience headaches, difficulty reading, and eye strain. They also may have a tendency to close one eye when viewing at distance or in bright sunlight.